A lot of people were really shocked when they found out I’m Canadian, Jewish, and half-Black. It was like, “Wait, what?” I didn’t put it on my mixtape cover like, “Hey, check out the new Canadian half-Black Jewish rapper!” I wasn’t advertising it, so people had to learn about me gradually.

I am biracial, with a Black American father, but I didn’t grow up in Black American culture. I didn’t have that cultural literacy or deep understanding of Black history and culture, especially the Black American experience. That’s why I could use American slavery in my lyrics without fully understanding the weight of it.

My mom is Jewish, and we had great Jewish dinners for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. We lived in an all-Jewish area in Forest Hill, and I went to a prominent Jewish school. Rapping started as a way for me to feel empowered. But when someone said, “You’re rapping like you’re always trying to free the slaves,” it showed they didn’t see me as part of their experience.

It wasn’t that I wasn’t cool; I just didn’t click with the kids who were considered cool.

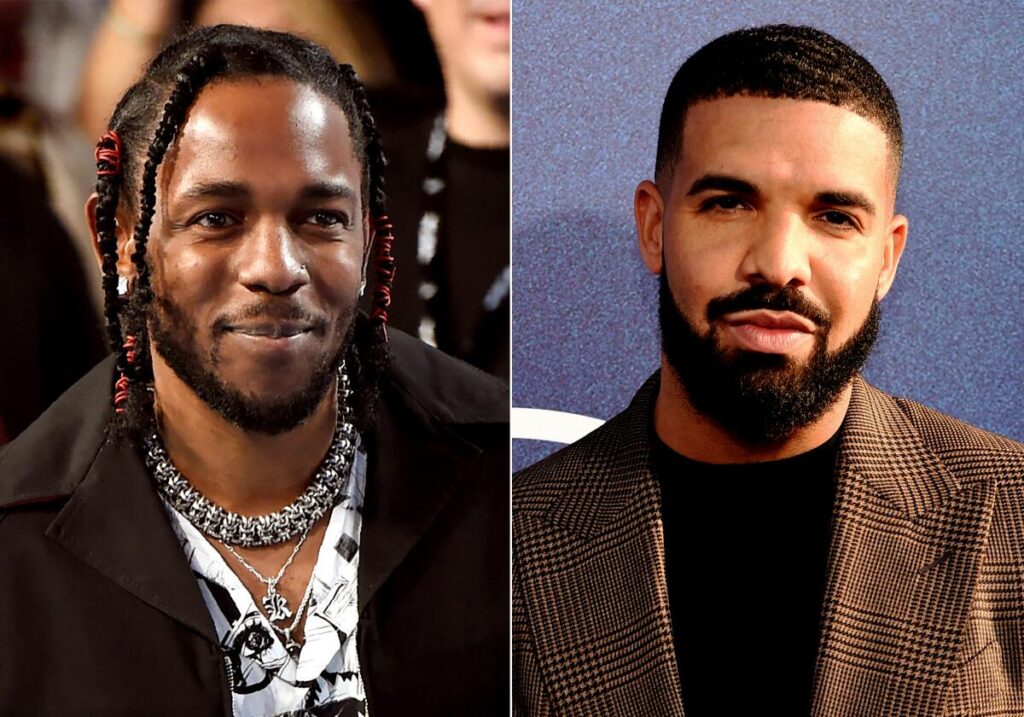

Everyone knows by now that Kendrick Lamar called me a colonizer on his diss track “Not Like Us,” and fans have been saying that he just voiced what people have been thinking for years. They claim I’ve been appropriating Black American culture, using it when it’s convenient and profitable.

But that’s just the beginning. Fans are also pointing out how I’ve disrespected Black American culture in weird ways, like making fun of Black trauma, disrespecting Black women, and hanging out with known racists. The list goes on. And now, in a classic move, I’m playing the victim, saying the Black American community shuns me because I’m biracial, Jewish, and Canadian.

Fans are quick to point out that the criticism of Drake has nothing to do with his race, nationality, or religion. It’s all about authenticity, and many believe Drake lacks it.

So, what did Drake do to disrespect Black Americans this time? What’s his real issue with Black America? Let’s dig into it.

“You can judge me if you want; that’s cool. Sooner or later, though, it’s going to be inevitable that your girlfriend’s going to be playing it, your mom’s going to want to listen to it, and your brother’s going to be like, ‘Can you get Drake to give me your autograph?’ So you might as well just get with it right now.”

First, let’s look at Drake’s background and upbringing, which might be the root of his insecurities. Instead of addressing these issues, Drake pretends to have had experiences and a past that he didn’t. He initially claimed he grew up very poor but later clarified that he lived in a rich neighborhood, just not as well off as his friends.

Then there’s the street rapper persona that Drake has been building over the past decade. He’s associated himself with rappers who actually lived that life, adopted their lingo, and sometimes even copied their style.

“Yo, Drake, watch your interview. He said he was supposed to contact one of my managers initially, but he didn’t do it, and that same week he plays.”

Drake pretends to have lived through tough experiences when he really hasn’t, almost like committing cultural stolen valor. For someone like Kendrick Lamar, who uses hip-hop to process his real-life struggles, it’s disrespectful for Drake to exploit the genre for his gain.

So what’s the deal with Drake’s identity crisis? Why does he feel the need to act like someone he’s not?

Identity Issues

Aubrey Drake Graham was born on October 24, 1986, in Toronto, Ontario. His father, Dennis Graham, is an African-American drummer from Memphis who played with Jerry Lee Lewis. His mother, Sandra “Sandi” Graham, is a Canadian Ashkenazi Jew who worked as an English teacher and florist. Dennis met Sandra at Club Blue Note in Toronto. They started dating, got married, but split when Drake was five.

After the divorce, Drake stayed with his mom in Toronto while his dad moved back to Memphis and spent several years in prison on drug-related charges. Due to financial and legal troubles, Dennis couldn’t return to Canada until Drake was an adult. Before his incarceration, he would visit Toronto and take Drake to Memphis during the summer.

Drake attended a Jewish day school and had a bar mitzvah. He lived in two neighborhoods: Weston Road in Toronto’s working-class west end until 2000, then in the affluent Forest Hill area. At 15, a friend’s father, an acting agent, helped Drake land a role on the Canadian teen drama series “Degrassi: The Next Generation,” where he played Jimmy Brooks, a basketball star who became physically disabled after being shot by a classmate.

When asked in 2011 about his early acting career, Drake said, “My mother was very sick. We were very poor, like broke. The only money I had coming in was from Canadian TV.” However, he later clarified that by “poor,” he meant in comparison to other kids at his school. “I went to school with kids flying on private jets. One guy’s family distributes Rolex in Canada, another owns Turtle Wax, and someone else’s family owns Roots Clothing. These kids were very fortunate. I never fit in. I was never accepted.”

To get a better sense of what he meant, here’s a clip of Drake talking about his childhood home: “What’s up, everybody? You’re chilling with me, Aubrey Graham. This is the living room. It’s nice and elegant, and I kind of leave this alone. It’s too much for me. This is our wonderful fridge, stocked. Start at the bottom and then through here. This is my comfort area. As you can see, I recently did laundry. This is actually a very nice couch. The shoes are a big thing. I got them from bottom to top.”

Drake has often mentioned that growing up biracial, Jewish, and Canadian made him feel like an outsider, making it difficult to make friends at school.

Melissa tweeted: “Drake claims he wasn’t cool in high school. What made you uncool?”

Drake responded, “It wasn’t that I wasn’t cool; it was that the kids who were cool weren’t necessarily on my wavelength, which made me sort of uncool, I guess. I just always felt like an outsider. When I was in Forest Hill, I was in an all-Jewish school. Being biracial but still Jewish, I was kind of connected to the kids but also sort of distant. And when kids are young, they don’t necessarily comprehend everything, so it can get a little cruel and mean.”

When asked if he got teased a lot, Drake replied, “Yeah, I definitely did.”

He also explained his upbringing: “Not like Orthodox Jewish or extremely religious Jewish. We celebrated every holiday, and I actually had a bar mitzvah. But, yeah, I was raised in a Jewish household. My mother always said, ‘You do what makes you happy, be with who you want to be with, and as long as you’re happy, safe, and not bringing trouble into my home, we’re good.'”

Despite these insecurities about his identity, Drake has often projected a tough guy persona that doesn’t align with his real-life experiences. Additionally, he has been accused of mocking Black American culture and seemingly antagonizing Black Americans on purpose. This behavior has led some rappers in the US to turn their backs on him, and it’s a key reason why he’s been labeled a “colonizer.”

Drake’s place in Black American hip-hop culture has always been contentious, particularly with his ongoing feud with Kendrick Lamar. Kendrick has criticized Drake, suggesting he shouldn’t use the n-word anymore because it doesn’t sound right coming from him. He even called Drake a colonizer, implying that Drake has been appropriating Black American culture for his own benefit, treating it like a costume he puts on whenever it’s convenient or profitable.

This accusation has sparked a massive debate among fans and critics alike. Many believe Kendrick’s words cut deep because they highlight a pattern where Drake seems to cherry-pick aspects of Black culture that boost his image or career. It’s definitely stirring the pot and making everyone take a closer look at Drake’s true relationship with the culture he claims to represent.

“The funniest thing to me right now is that whether you’re a Drake fan, Kendrick fan, anybody, the way that Drake responds to being able to say the n-word… How do you defend that? You either double down and say how Black you are, which is weird, or you completely ignore it as Drake often has. Everybody reacted to this Drake line, ‘Metro, shut your ass up and make some drums.’ It was hilarious. But now everybody’s reacting to this Kendrick line, ‘I even hate the way you say the n-word, but that’s just me.’ I guess hearing this line, you only can take it two ways: You either look at it like Drake’s Black, he can say the n-word, it’s not his fault that he’s light-skinned, or you agree with Kendrick and his implication that Drake partakes in the exploitation of Black culture. Because Kendrick didn’t say, ‘Oh, Drake’s not Black.’ He didn’t say, ‘Drake is mixed, and Drake is light-skinned.’ He said, ‘We don’t want to hear you say the n-word no more. We don’t want to hear it.’ That is very much a cultural implication more so than an identity or ethnic implication. It’s more so talking about exploitation of the culture of hip-hop, which is based and rooted in American Blackness.”

However, Kendrick isn’t the first one to call out Drake for seemingly disrespecting Black American culture while profiting from it. For years, there have been whispers and outright accusations that Drake cozies up to rap artists, replicates their sound and style for his own gain, and then moves on to his next project. Big names like Earl Sweatshirt, Rick Ross, and Pusha T have all talked about this pattern, with claims of Drake being a culture vulture swirling around for at least a decade.

Back in 2015, former Odd Future member Earl Sweatshirt was not impressed at all when Drake featured Kodak Black’s “Skrt” on episode 6 of OVO Sound Radio on Beats 1 and later shared a clip of himself grooving to it on his private jet. This prompted Earl to tweet, “Drake found Kodak Black. Shaking my head. Welp.” And then Earl responded to another user saying, “Drake can be a bit of a vulture on young rap artists, and I don’t want Lil Kodak to be a victim of it.”

Next up, we’ve got Rick Ross, who recently branded Drake a “white boy.”

“Damn white boy, Kendrick done bust you in the head before y’all even finish the publishing splits.”

Back in April, Ross also responded to Drake’s diss on “Push-Ups” with a track called “Champagne Moments,” released just hours after “Push-Ups” was leaked. On “Champagne Moments,” Ross raps, “Flow is copy and paste. Weezy gave you the juice, another white boy at the park, wanna hang with the crew.”

This controversy has ignited a major debate among fans and critics alike. Many believe Kendrick’s words strike a chord because they highlight a recurring pattern where Drake appears to selectively adopt elements of Black culture that enhance his image or career. It’s certainly stirring up controversy and prompting a closer examination of Drake’s genuine connection to the culture he professes to represent.

“The funniest thing to me right now is that whether you’re a Drake fan, Kendrick fan, or anyone else, the way Drake responds to the criticism about his use of the n-word is telling. How do you defend that? You either double down on asserting your Black identity, which is awkward, or you ignore it altogether, as Drake often has. Everyone reacted to Drake’s line, ‘Metro, shut your ass up and make some drums.’ It was funny. But now everyone’s reacting to Kendrick’s line, ‘I even hate the way you say the n-word, but that’s just me.’ This line forces you to take one of two positions: either you believe Drake’s Blackness justifies his use of the n-word, regardless of his light skin, or you side with Kendrick’s implication that Drake exploits Black culture. Kendrick didn’t say, ‘Oh, Drake’s not Black.’ He didn’t say, ‘Drake is mixed, and Drake is light-skinned.’ He said, ‘We don’t want to hear you say the n-word no more. We don’t want to hear it.’ This is more a cultural critique than an ethnic one, highlighting the exploitation of hip-hop culture, which is deeply rooted in American Blackness.”

However, Kendrick isn’t the first to accuse Drake of disrespecting Black American culture while profiting from it. For years, there have been murmurs and outright allegations that Drake associates with rap artists, mimics their sound and style for his benefit, and then moves on to the next project. Big names like Earl Sweatshirt, Rick Ross, and Pusha T have all discussed this pattern, with accusations of Drake being a culture vulture circulating for at least a decade.

Back in 2015, former Odd Future member Earl Sweatshirt expressed his displeasure when Drake featured Kodak Black’s “Skrt” on episode 6 of OVO Sound Radio on Beats 1 and later shared a clip of himself enjoying the song on his private jet. This led Earl to tweet, “Drake found Kodak Black. Shaking my head. Welp.” He later responded to another user, saying, “Drake can be a bit of a vulture on young rap artists, and I don’t want Lil Kodak to be a victim of it.”

Then there’s Rick Ross, who recently called Drake a “white boy.”

“Damn white boy, Kendrick done bust you in the head before y’all even finish the publishing splits.”

Back in April, Ross also responded to Drake’s diss on “Push-Ups” with a track called “Champagne Moments,” released just hours after “Push-Ups” was leaked. On “Champagne Moments,” Ross raps, “Flow is copy and paste. Weezy gave you the juice, another white boy at the park, wanna hang with the crew.”

Remember the drama over the cover art for Pusha T’s diss track “The Story of Adidon”? That wasn’t AI trickery; it was actually Drake in blackface. The photo was taken by photographer David Leyes back in 2007 when Drake was still chasing his acting dreams, long before he got into rap. Fans were outraged. The backlash was intense, with both fans and celebs criticizing Drake for this controversy. It really stirred things up and added even more fuel to the debates about his place in Black American culture.

People were asking, “What are you doing, Black man? And don’t say you were young. You were old enough to know better. Where was your mother to tell you not to do this? This picture is disgusting. What were you thinking? Is this what you had to do to make it on the radio? So anything you say now isn’t really from your heart. Are you really that stupid to wear blackface with a big smile?”

Drake tried to clear things up by saying the blackface photo was meant to highlight the unfair treatment of Black actors in the entertainment industry. He wrote, “The photos represented how African-Americans were wrongfully portrayed in entertainment. This was to highlight our frustrations with not getting a fair chance in the industry and to show that the struggle for Black actors hasn’t changed much.”

But here’s the kicker: despite his explanation, Drake kept making questionable choices. On his 2023 album “For All The Dogs,” he rapped in “Slime You Out,” “Whipped and chained you like American slaves,” referring to buying cars and jewelry for women. In his Kendrick diss track “Family Matters,” he told Kendrick, “You always rapping like you’re about to get the slaves freed.”

Fans have pointed out how insensitive and cringeworthy it is to use slavery as a punchline. One fan said, “Drake making jokes about the freedom of slaves shows he knows nothing about our ancestors, Black pain, or slavery. Imagine if Kendrick joked about the Holocaust and Drake’s ancestors. It wouldn’t be funny, right? But Black pain is?”

To make things worse, Drake has been seen associating with controversial figures known for their racist remarks. In December 2021, he faced heavy criticism for collaborating with country star Morgan Wallen, who was caught on video using a racial slur. Despite the backlash, Wallen’s popularity surged, and his album continued to dominate the charts.

Wallen’s apology, claiming he was just talking dumb stuff with his friends, seemed insincere. When asked if he understood why using the n-word upset Black people, he said, “I don’t know how to put myself in their shoes because I’m not, but I do understand.” It was the classic “I’m sorry I got caught” kind of apology.

Drake’s willingness to associate with people who disrespect his Black roots raises questions. Is he cozying up to racists to provoke a reaction, or does he actually share their views? The company he keeps continues to stir controversy and provoke debate among his fans and critics alike.

Despite all the controversy, Drake went ahead and teamed up with Morgan, even releasing the video for his song “You Broke My Heart,” featuring Morgan prominently. To ensure no one missed it, Drake filled Instagram with photos of them together, seemingly trying to make a point about their friendship. To make matters worse, the video included two white girls mouthing the lyrics, making it even more awkward as they had to censor the n-word each time Drake said it.

But this issue with Morgan Wallen is just the beginning of Drake’s questionable connections. Remember when Rick Ross got into trouble in Vancouver earlier this month, allegedly involving Drake’s affiliates? Ross was in Vancouver for a music festival and played Kendrick’s diss track “Not Like Us,” which didn’t go down well with the locals. Soon after, Ross and his crew were attacked backstage. It turns out those locals were members of the notorious Hell’s Angels biker gang.

Drake has been friendly with the Hell’s Angels for a while, even mentioning them in his songs and on social media. However, the Hell’s Angels have a history of racially motivated attacks. Just last September, three members were involved in a brutal attack on three young Black men in San Diego, California.

Drake was later caught liking a post about the attack on Rick Ross, which led podcaster Dwan Brown to share a photo of Drake wearing a Hell’s Angels shirt. Brown captioned it, “Rick Ross was attacked by a racist Canadian gang with direct ties to the Hell’s Angels while being called the n-word in the attack. Drake is also an open Hell’s Angels supporter. Drake should be forced to denounce white supremacy and white supremacist gangs. Drake’s connection to Hell’s Angels leader Andrew Keru should be investigated along with his connection to the [redacted] gang.”

Andrew Keru is a shady Canadian millionaire known for throwing extravagant parties. He has a criminal record, with charges ranging from gun possession to domestic violence. Rumor has it he’s involved in even more serious criminal activities and is closely associated with the Hell’s Angels. Drake has been close to them for years to boost his street credibility, even featuring Keru in the music video for his diss track aimed at Kendrick, “Family Matters.”

Drake has lied about his upbringing, stolen flows from Black artists, referenced slavery in his songs, and associated with people accused of racism. Fans are starting to wonder if Drake gets some sort of thrill out of antagonizing and mocking Black Americans.

Recently, Drake was caught disrespecting Black Americans again during a debate sparked by Kendrick’s “Not Like Us” track and video. He claimed that Black American rappers and hip-hop fans are just mad because a Canadian Jew is doing more for the culture than they are.

Drake doubled down. A video circulating shows a DJ in Dubai ranting against Kendrick, mocking Black American rappers and fans, and claiming that Drake is the one who united them, not Kendrick.

“Kendrick won. Very cute moment. But guess what else? For the last 15 years, guess who’s been killing it? It’s about time somebody not Canadian, right? Right, a Canadian’s been running the rap game, half-Jewish. That’s why they mad. That’s why they mad. All the gangsters are on the streets in LA. Crips and Bloods united because of this man. My man brought the city together. He’s doing more for them. Oh my God, it’s crazy. It’s crazy. Toronto all day. I love you.”

Drake was caught liking this video, and fans are saying this is further proof that he has no respect for the culture and people he’s been profiting from for years.

One fan wrote, “I believe he hates Black Americans because we don’t claim him. He’ll never get our approval as a whole, ever, and it eats him up inside. He’s a fraud with identity issues who likes to pretend to be a hood Black man for profit, even though we all know he grew up in a white Jewish suburb in Canada. He’s not one of us and never will be. And no, I don’t care about this cornball spending his summers here with his deadbeat daddy. That doesn’t make him Black. I believe he’s always felt some type of way about us, but he couldn’t express it before because he needed us as props to make his money first. Now that he’s at a point in his career where he feels untouchable, he’s finally decided to be openly disrespectful towards us.”

So, what’s your take on this whole colonizer narrative? Is Drake really antagonizing Black Americans on purpose? Do you think he even understands why Kendrick called him a colonizer? Leave your thoughts in the comments section below